Yearbook 2012

Italy. Silvio Berlusconi’s resignation as prime minister in November 2011 – a result of the euro crisis – was assumed to be the end of a long political era, but new surprises would come a year later. The successor, economist Mario Monti, with his unpolitical so-called expert government quickly presented his first crisis package with huge savings. It included deteriorated pension conditions, increased retirement age and stricter excise taxes.

Before the New Year 2012, Parliament approved the state budget in a vote of confidence. However, Monti was able to obtain broad support only after both the left and the right forced the government to water down the proposals on some points.

Foreign media’s interest in Italy diminished at a time when the contentious Berlusconi had now left the spotlight. However, big headlines were created in connection with the luxury ship Costa Concordia’s grounding and sinking on 13 January. The circumstances surrounding the tragic and “unnecessary” accident, which required 32 fatalities, were remarkable, and many observers marveled at the captain’s behavior of leaving the route to allow people on land to view the ship more closely. Trials against the captain and the shipping company were expected earlier in 2013.

- AbbreviationFinder.org: Provides most commonly used acronyms and abbreviations for Italy. Also includes location map, major cities, and country overview.

In addition to the approved austerity measures, the government also presented a program of structural reforms and economic stimulus in January. But proposals aimed at increasing competition in, among other things, the taxi industry and pharmacies led to union protests and strikes. The international financial market remained skeptical of the government’s goal of eradicating the budget deficit within one year, but Monti still managed to strengthen the world’s confidence in the country’s politics. The Italians, too, according to a series of opinion polls, had much greater confidence in the Monti government than for the political parties.

The leading government party until the end of 2011, the People of Liberty (Il Popolo della Libertà, PDL), was on the downhill, speckled by the ongoing legal proceedings against leader Silvio Berlusconi. Local elections in May and regional elections in Sicily in October, as well as several opinion polls, confirmed the parties’ crisis. At the end of the year, PDL appeared to have lost more than half of its supporters since the 2008 election, while LN lost half since Bossi resigned in April.

The Democratic Party (Partito Democratico, PD) on the left was the biggest by all measurements, while the most obvious sign of the Italians’ “political contempt” was the well-known comedian Beppe Grillo’s populist anti-political movement Five Star (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S). According to most opinion polls, the party was close to 20% the country’s second largest.

For a long time, it was unclear what Berlusconi planned for the future. In June and July, he had declared that he wanted to become head of government again. Disclosures about new corruption deals within PDL, including however, in the Lazio (Lazio) region, the constant court proceedings and mistrust of his ability to organize the economy led to an increasing number of people in Berlusconi’s surroundings trying to make him realize that the task was becoming too difficult.

The legal process that is considered to have hurt Berlusconi’s reputation most is “the Ruby case”, the allegations that he paid for sexual intercourse with a then 17-year-old Moroccan and later used his influence to get the police to release her when she was arrested on suspicion of theft. In April, Berlusconi had personally attended a hearing, which was unusual, but for the rest of the year his lawyers managed to delay the case.

A corruption target originating in 1997 ended the same way as a number of other lawsuits against Berlusconi. The target was set in February because too much time had elapsed. It was suspected that the politician had bribed British lawyer David Mills to testify falsely in a previous lawsuit. In October, however, the first convict against Berlusconi fell since he resigned. It was a tax evasion in connection with his media company Mediaset buying TV rights to American films. He was initially sentenced to four years in prison, which was reduced to one year under a law aimed at reducing overcrowding in prisons. The case would be tried in a higher instance.

Shortly after the verdict, Berlusconi realized that he would not seek the post of prime minister at the 2013 parliamentary elections but remain in politics. PDL Party Secretary Angelino Alfano was seen as a strong candidate as a new party leader. But in early December, Alfano announced that Berlusconi had changed his mind again and planned to stand. One day later, December 6, PDL abstained from voting for Monti in two vote of confidence in protest of the economic austerity. However, the proposals were accepted, but Monti submitted his resignation application to President Napolitano two days after the missing PDL support.

Due to Monti’s departure, the 2013 election was moved from April to February. The days before Christmas, when the 2013 budget was adopted, he announced that he was willing to lead the next government as well. And just before New Year’s Eve, Monti said he was gathering a coalition of middle parties in the election. Berlusconi’s political maneuvers had thus led to two strong opponents; left candidate as head of government, PD leader Pierluigi Bersani and Monti.

Another event that attracted a great deal of international attention was the long prison sentences in October against six of Italy’s leading seismologists and geologists as well as a civilian official for gross negligence to the death of another. The convicted were deemed to have misjudged the risks and given too reassuring news before the big earthquake in 2009 in the city of L’Aquila that required 309 deaths. The verdict, which was not expected to be held in a higher instance, was sharply criticized by researchers around the world who pointed out that earthquakes cannot be accurately predicted.

Rome – economy and institutions

Banking and insurance, trade and services, public administration, tourism and film production characterize the city’s economy, which has a volume equivalent to 7% of Italy’s gross domestic product. During the 1980’s, public administration has shrunk in favor of advanced service and high-tech manufacturing companies, not least in the IT industry, and the capital is Italy’s third most important industrial city (after Milan and Turin). The city is also the seat of the government and the two chambers of parliament, as well as of Italy’s many state-owned enterprises. The old university La Sapienza (grdl. 1303) has approx. 200,000 students. In addition, the newer and smaller universities Roma II are located in the outskirts of Torvergata and Roma III in the industrial district of Ostiense, as well as the private LUISS and Università Cattolica. The city also has a number of papal colleges as well as in hundreds of archives, libraries and museums. Tourists are attracted by Rome’s immense amounts of art treasures and by the city’s rich history and colossal cultural heritage, and Rome’s status as the Pope’s city attracts millions of pilgrims every year.

Rome – cityscape

Despite renovations, street breakthroughs and point-by-point new buildings from 1870 to the mid-1930’s, Rome’s historic city center, Centro storico, appears, which includes Marsmarken and the neighborhood Trastevere, still quite homogeneous and is especially characterized by construction from the Renaissance and Baroque. Everywhere you find relics from much older periods in the form of entire buildings, such as the Pantheon, ruins and building remains or streets, such as the current Via del Corso, which is identical to the ancient Via Lata.

The city center was until approx. 1970 marked by great social spread. However, the development of the real estate market and changed business structures have meant that the economically disadvantaged have had to move to the suburbs, while the homes, workshops and grocery stores in the center have been transformed into offices, wealthy apartments and specialty shops.

Due to environmental problems, the area is closed to outside private car traffic.

Outside the city center, densely populated residential areas extend to all sides, but primarily to the south and east. Immediately connected to the Centro storico, the districts between the Quirinal Palace and the Stazione Termini (1951), around Via Veneto and in the Prati area north of the Vatican, emerged in 1870-1900. Via Veneto, famous in the 1960’s as the setting for “the sweet life”, is still known for its exclusive hotels and restaurants, although the atmosphere is less hectic. With its wide, straight chessboard-patterned streets and spacious apartments, Prati is one of the favorite residential areas of the middle class.

South of the city center, but within the major ring road is the EUR district, which with its cool modernist building style stands in stark contrast to the rest of the city. An exceptionally tight planning and management for Rome has made the EUR a relatively green and well-functioning district. The eastern districts of Prenestino, Tuscolano and Tiburtino, with their high-rise buildings, are examples of the speculative construction of the 1950’s and 1960’s. In the latter two, however, there is also high-quality non-profit construction. More privileged neighborhoods from the same unplanned period of expansion are Aurelio, Monteverde Nuovo and Portuense to the west and south and the more exclusive Monte Mario, Via Cassia and Vigna Clara to the NW. The well-to-do neighborhoods are Parioli north of the large Borghese garden and Aventino south of the city center. Since the 1950’s, the preferred form of housing for the more affluent has been detached 4-5 storey properties with up to ten apartments.

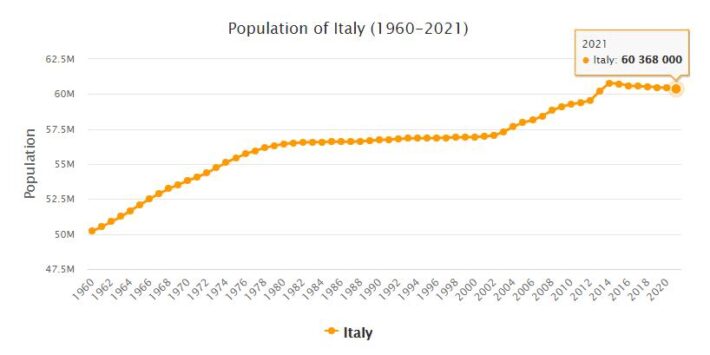

Population 2012

According to countryaah, the population of Italy in 2012 was 60,578,383, ranking number 23 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.420% yearly, and the population density was 205.9512 people per km2.