Yearbook 2012

Myanmar is a country located in Asia. During the year, political reforms continued towards increased democratization of Burma that began in 2010. But while the outside world and the country’s own opposition welcomed the political thaw, it was also stressed that much remained to be done before Burma could be considered a democratic country. The driving force for increased openness was first and foremost among the country’s rulers, President Thein Sein and within the opposition were former NLD leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

The need to resolve the serious conflicts that existed between the regime and several of the country’s ethnic minorities was raised in connection with the reform work. Cease-fire agreements were concluded in several places, but in the Rakhine province, also called Arakan, in the west, ethnically-related violence between Buddhists and Muslims erupted, particularly the vulnerable Muslim group Rohingya, with nearly a few hundred dead as a result and a large refugee stream, also over to neighboring Bangladesh.

- AbbreviationFinder.org: Provides most commonly used acronyms and abbreviations for Myanmar. Also includes location map, major cities, and country overview.

During the first month of the year, the government issued two major amnesties for prisoners. The first took place on Independence Day, January 3. At that time around a thousand prisoners were released, but only an estimated maximum of thirty were to be considered political prisoners. The president also converted the death penalty to prison and shortened the prison sentence for more than 20 years. However, in the second amnesty ten days later, significantly more political prisoners were released. Human rights organizations estimated the number to be between 130 and 288 out of a total of about 650 released. Among the released were several well-known dissimilar journalists, bloggers, leaders of ethnic minorities and human rights activists and others. Among others, Min Ko Naing, leader of the 1988 student uprising against the then military regime, was released, and Buddhist monk Ashin Gambira, one of the leaders of the 2007 rebellion,

After the second amnesty, US President Barack Obama announced that the United States would establish full diplomatic relations with Burma and that ambassadors should be installed in the two countries.

Burma’s opening to the outside world continued when British Foreign Minister William Hague visited the country in January. The last time a British Foreign Minister visited Burma was in 1955. Hague praised recent developments but also said that much remained before Burma and Britain could fully normalize relations, including all political prisoners must be released, the upcoming parliamentary election elections must be free and fair and human rights groups must gain access to the areas where ethnic conflicts are ongoing.

The EU decided to lift some of the sanctions against Burma, among other things a number of civilian Burmese ministers could again get visas to EU countries. Norway and Australia also announced that some sanctions against Burma’s leadership would be eased.

A great deal of attention was given to the election elections to Parliament and local assemblies to be held on April 1. The elections were seen as a test of the government’s willingness to reform when NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi chose to run for office in a constituency in Rangoon’s suburbs.

On January 12, the government announced that a cease-fire agreement had been concluded with the Karengerillan KNU, which has been fighting the regime for increased autonomy or independence since 1948. While the KNU’s management described the agreement as an important step toward peace, parts of the guerrillas doubted that the agreement was not meant an immediate retreat by the government soldiers from the Karen People’s area of northern Burma. According to President Thein Sein, six out of eleven ethnic groups had now concluded similar ceasefire agreements with his government. Among the groups that did not agree to the settlement were the Kachin People’s Independence Organization KIO and the Mon People’s Movement NMSP. A seventh group joined the ceasefire in March.

The hopes that the important election elections on April 1 would be free and fair were reinforced when President Thein Sein in March invited election observers from, for example, the United States, the EU and Southeast Asian countries within the ASEAN cooperation organization. Critics, however, felt that the invitation had come way too late and that election observers would be too few to guarantee an international standard on the elections. The filling elections that were intended to be held in Kachin had to be postponed due to fighting between government forces and the guerrilla group KIA. The fighting continued despite the president calling for the army to withdraw, indicating that the old General Thein Sein did not have full control over the military at the local level.

Aung San Suu Kyi was allowed to speak in state-owned media for the first time, but she said afterwards that a statement about the lack of legal security had been cut. The NLD leader had on several occasions also criticized the fact that a quarter of the seats in Parliament are reserved for the military and had demanded a constitutional change on this point.

In March, the president signed a law that allowed the formation of trade unions and opened up that strikes could also be legal.

In March, the International Maritime Law Court ITLOS granted Bangladesh the right to maritime areas in the Bay of Bengal, which both Burma and Bangladesh had claimed. The areas are rich in fish and are also believed to contain oil and natural gas. The dispute had been going on since 2009.

The opposition NLD (National Democracy Association) won a very big victory in April when they received 43 of the 45 seats to be elected in the election. The military-supported government party USDP (Union Solidarity and Development Party) got a seat and the Shan People’s Party SNDP (Shann Nationalities Alliance for Democracy) won a place. NLD also won in the new capital Naypyidaw, where the vast majority of residents are civil servants who could conceivably give their support to the USDP. The government quickly accepted the election result.

When the new MPs, including Aung San Suu Kyi, were to take their seats at the end of the month, problems arose when they could not accept the oath of allegiance to the constitution which they considered undemocratic, partly because of the military’s reserved seats. They wanted to change the oath from “protecting” the constitution to “respecting” it. After a while, however, the new members agreed to swear the oath as it was because they otherwise risked immediately colliding with the hawks within the government that the president had to deal with. Aung San Suu Kyi said this was “the will of the people”.

As the first European head of government since the military junta’s takeover of Burma in 1962, Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron visited the country on April 12-13. After talks with Thein Sein and Aung San Suu Kyi, Cameron gave his support to the NLD leader’s line, namely to temporarily suspend the sanctions against Burma but not abolish them. One exception was the arms embargo that would remain. In this way, Burma’s pursuit of increased democracy and strengthened human rights would be encouraged, while the sanctioning tool could be quickly resumed if the Burmese government deviated from the course.

Following the election, the United States decided to ease a number of sanctions against Burma, such as entry bans for government ministers. In May, the United States also lifted some restrictions on US companies’ terms of operation in Burma. In April, the EU lifted all sanctions except the arms embargo for a year, to then evaluate the situation. As the first foreigner, UN chief Ban Ki Moon was allowed to speak before Burma’s parliament at the end of April/May.

In June, a prolonged period of widespread ethnic violence between Buddhists and Muslims broke out in Rakhine Province in northwestern Burma. The outbreak of violence was triggered by a gang rape and murder of a Buddhist girl by three Muslim men. In what looked like a revenge attack a few days later, a bunch of Buddhists ripped ten Muslim men out of a bus and killed them. The travelers were later reported to have been pilgrims from another part of the country. The three youngsters who carried out the group rape and murder were jailed. Two were sentenced to death and one died in police custody.

A wave of violence, looting and arson spread across the province, where Buddhists and, above all, Muslim Rohingya stood against each other. President Thein Sein introduced a state of emergency and additional military was called. The president warned that the country’s political and economic reforms could be threatened by the wave of violence. On June 11, the UN reduced its presence in Rakhine to a minimum. At least 78 people were killed and as many as 90,000 were evicted from their homes according to the UN before the violence could be stopped.

In mid-June, Aung San Suu Kyi made a notable trip to a number of European countries – Switzerland, Norway, Ireland, the United Kingdom and France. In Oslo, she finally got the opportunity to keep her noble number, something she couldn’t when she got the award in 1991 because she was then placed under house arrest. Her two sons at that time received the Peace Prize in her place. In London, Aung San Suu Kyi was the first non-head of state or government to speak to the entire British Parliament when both the lower house and the upper house gathered to listen to her.

In August, the government announced that all pre-censorship of print media would be abolished, but that the review of the publications would be ex post. In the same month, President Thein Sein carried out a reform of government to strengthen the reform-minded faction within the government against the conservative and reform skeptic.

In October, fighting between Muslims and Buddhists caught fire again in Rakhine. Another 90 people were killed and more than 22,000 had to flee their homes. In total, over 100,000 people had now become homeless due to the ethnic violence in the province.

Foreign political leaders continued to flock to Burma in the autumn to express their support for the democratization process and to explore the possibilities of trade with Burma. Among the visitors in November were Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt and EU Commission President Jos谷 Manuel Barroso. The EU promised Burma over US $ 100 million in development aid.

In November, Burma was visited by US President Barack Obama. He offered the country friendship and cooperation in exchange for more political and economic reforms. At the same time, Obama called for reconciliation between Buddhists and Rohingya in Rakhine. Before the visit, several hundred interns were released from Burma’s prisons. It was not known if any of these were political prisoners.

In December, the government announced that privately owned newspapers would be allowed again from April 1, 2013. The last Burma had a privately owned newspaper was 1964.

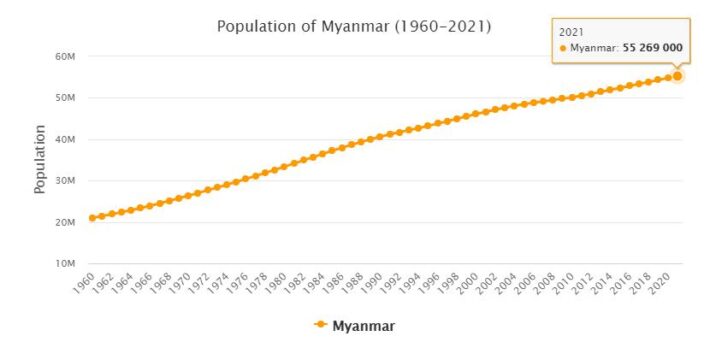

Population 2012

According to countryaah, the population of Myanmar in 2012 was 52,680,615, ranking number 25 in the world. The population growth rate was 0.810% yearly, and the population density was 80.6391 people per km2.