Yearbook 2012

Congo. By the November 2011 presidential and parliamentary elections, President Joseph Kabila had consolidated his hold on power. But the election had been bordered by accusations of cheating and other irregularities. In addition, the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) first presented the formal election results on February 1, 2012. CENI then confirmed that Kabila had won the presidential election with close to 49% of the vote before Etienne Tshisekedi, leader of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), which received just over 32%. In the parliamentary elections, the parties supporting Kabila’s own majority in the National Assembly, but the president’s own party, the People’s Party for Reconciliation and Development (PPRD), received only 63 seats, 48 fewer than in 2006. The UDPS became the largest opposition party with 41 seats. 17 mandates could not be added due to accusations of violence and cheating. Tshisekedi, who had been placed under house arrest after the election, urged his party mates to boycott the work of the National Assembly, but all but three UDPS members took their seats. According to a UN report in March, forces loyal to President Kabila had killed at least thirty people in Kinshasa around the 2011 election.

- AbbreviationFinder.org: Provides most commonly used acronyms and abbreviations for Democratic Republic of the Congo. Also includes location map, major cities, and country overview.

A difficult blow for President Kabila was when his closest adviser, Augustin Katumba Mwanke, died in a plane crash on February 12.

In the troubled eastern parts of the country, the situation deteriorated drastically in April when several hundred, perhaps a thousand, government soldiers deserted. The soldiers had previously belonged to the Tutsid-dominated rebel movement CNDP (Congrès national pour la defense du peuple), which had been incorporated into the government forces three years earlier. Through a peace agreement in March 2009, their army unit was given responsibility for North Kivu, the province where the CNDP had previously fought the government army and shot itself at the rich natural resources. Their leader, Bosco Ntaganda, had been appointed general despite being called on by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague since 2008 on suspicion of war crimes.

Initially, it was claimed that it was a soldier revolt that was triggered by dissatisfaction with unpaid wages and poor living conditions, but in May it was clear that it was more than that. Then a new rebel group was formed, called the Movement on March 23 (M23) after the date the 2009 peace treaty was signed. It was speculated as to why the uprising started right then. One reason seemed to be that the Army unit was about to lose its strategic location by relocating it to another province. In addition, there were signs that the Kinshasa government was preparing to arrest Ntaganda to bring him to trial in Rwanda’s homeland.

The violence gradually increased and the M23 took control of increasingly large areas near the border with Rwanda and Uganda. A ceasefire announced between the government army and the M23 in July did not last long. From April to November, about half a million people were displaced. Although M23 was formally led by Colonel Sultani Makenga, most observers were convinced that it was Ntaganda who had the highest command. In June, information leaked to the media from the report that the United Nations Expert Group for the Congo (Kinshasa) would submit to the Security Council. In it, Rwanda, and even Uganda, were accused of supporting M23. In an even more detailed report in October/ November, UN experts went even further, claiming that M23 was in principle under the command of Rwanda’s defense minister and that both Rwandan and Ugandan soldiers fought alongside the rebels. Rwanda would also have helped M23 recruit new combatants. Both Rwanda and Uganda denied the charges.

In November, the M23 advanced and entered Goma, the capital of Northern Kivus, and the rebel force threatened to continue to Kinshasa to overthrow Kabila. However, the rebels left the city in early December, after President Kabila and Makenga agreed on a peace plan. However, the situation in the area remained tense. In several cities in Northern and Southern Kivu, the people protested against the M23, but also against Kabila and the UN force MONUSCO, which failed to protect them.

The situation remained uncertain and M23 threatened to resume fighting if Kabila failed to fulfill its promises or refused to continue the negotiations. On the last day of the year, the UN Security Council decided to impose sanctions on several of the leaders of the M23 and the hutumilis FDLR. According to them, they were charged with travel bans and had their financial assets frozen.

A clear signal to suspected war criminals about what they could expect was when the ICC sentenced Thomas Lubanga, leader of the UPC militia, to 14 years in prison for July having recruited and used child soldiers in the fighting in the Ituri district in 2002–03. It was the first sentence that the court handed down since it was established in 2002. However, the sentence was significantly lower than many had expected, the prosecutor had pleaded to 30 years in prison. Another defendant, Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui – also he from Ituri – was acquitted in December, when the judges considered that the evidence against him was insufficient. He had been charged with ordering a massacre in the village of Bogoro, where at least 200 people were killed in 2003.

Doctor Denis Mukwege, who has become known around the world for his work in helping Congolese rape victims, was subjected to a murder trial in October in the city of Bukavu. He survived, but one of his employees was killed.

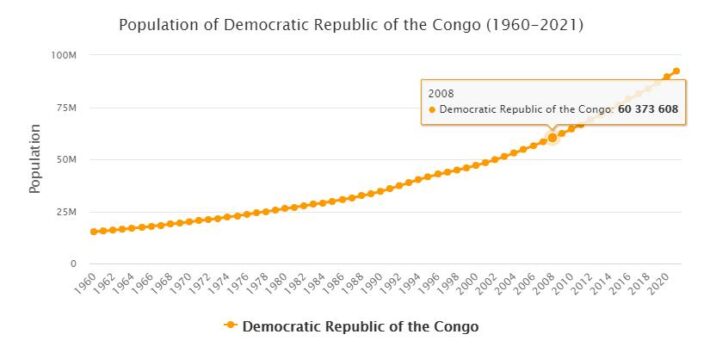

Population 2012

According to countryaah,the population of Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2012 was 76,244,433, ranking number 19 in the world. The population growth rate was 3.380% yearly, and the population density was 33.6316 people per km2.